Good Looking Teacher

By Melissa Knox

Teaching for the very first time, I alternated between two long, high-waisted Paul Stuart knife-pleat skirts, which I paired with Victorian shirtwaists. My hair in a bun so tight my scalp hurt, I donned black wing-tip pumps.

Meeting me on the way to class, one of my male students elbowed me, wanting to carry my books, and smirked when I offered a demure “no, thanks.” Like any household pet, a student sniffs out self-doubt. Lack of confidence stuck out all over me.

When the kid did well on his entrance exam, I told him we were moving him into the more advanced writing section. What a sigh of relief I breathed—he’d be out of my hair forever.

“Gee, I dunno,” said the kid, “I wanna stay. You’re such a good-lookin’ teacher.”

Can’t believe the kid said that? This was in 1983. He departed with a nod and a wink.

Sometimes the problem’s not a crush, but a business-minded kid. When I taught at a fashion institute, a young man sidled up and whispered “feel this”—while thrusting a swatch of, as he put it, “butter-soft” leather at me. In return for making me a leather suit “at cost,” he wanted a passing grade.

I was tempted, reader, but I resisted.

There are students who hang on your every word, come to office hours so often you feel you can’t walk down the hall without running into them, or just seem strange.When such a student arrives in my office, I leave my door wide open, placing the only other chair in the room close to the table, rather than my desk, so that there’s always a good two feet between me and whatever fantasy is running through the kid’s head.

“I just have stage fright when I come to see you!” said one young woman, eyes shining.

To such remarks, I usually reply, “The only difference between you and me is an additional 45 years of reading.” Dissolve that pedestal some of them put you on or run the risk of allowing them to cast you not as God but the devil.

Back when I was twenty-five, I had a crush I tried to hide on my esteemed professor. In Columbia University’s Philosophy Hall, he liked to swing his legs up on the desk, lean back in his swivel chair, and cock his head ironically. He’d written a book I thought brilliant. He knew much more than I did, and I believed he knew much more than he actually did know. From my current vantage point of sixty-five, I can see how easy it is to get a twenty-five-year-old person to feel she knows nothing.

Napoleonic in height, my professor looked up, literally, at me, and his gaze roamed. I wanted to continue admiring him, so pretended he wasn’t staring at my breasts. I wanted him to be interested in my ideas, the ones I’d typed and re-typed on my IBM Selectric, the ones on those pages he was now holding in his hand. I practiced the “it’s not there” form of problem-solving and went gamely into his office with the thought that I ought to get my paper that he’d just grade. I thought I would learn something from him.

There was the nagging fact that my blood raced when I saw him. The sight of him made my palms sweat.

I cringe when I remember how witty I thought him: When I ran into him in the checkout line at the local grocery store, he was buying ice cream and I was buying broccoli. He frowned at my broccoli and said, “I win!”

Had he actually laid a glove on me, I’d probably have felt disgust. Not that I’d never been with a man, but the men I’d been with were boys my age. Temples greying, overstuffed bookshelves sagging, desk piled with manila folders, my professor seemed an idol enshrined in scholarship, waiting to be revered. My attraction lay in my ability to keep him on that pedestal, clay feet constantly on display but unnoticed by me.

I sat by his desk as he flipped through my paper, hoping he was finding my ideas original, brilliant. At least not dumb.

“Ya know, I’m finding out a lot from the papers you write!”

“You are?” I sat up straight. Maybe I’d win an award. I saw myself typing an extra line on my CV.

“Yeah!” He winked. "Your personalities."

I leaned forward, waiting to hear that I’d be considered for the next Marjorie Hope Nicholson scholarship.

“Yeah, Ms. Knox, you’re spread-eagled on the page!”

I remember staring straight ahead, rising to my feet without knowing what I was doing, heading—hurtling—down the hall to the classroom, for his class was about to start. I pulled out my chair at the long seminar table and sat down. It seems to me now that I’d actually managed to suppress his words by the time I’d retrieved from my bookbag my notebook, pens, and poetry anthology. Shame and shock flooded through me, and something else I didn't recognize back then—extreme disappointment. But I was determined to feel exactly as I had felt before. I wanted to go on admiring him—I would soldier on as his disciple, because how else would I exist? I needed an example of scholarship, and he was it.

The understanding that comes with age—that here was a depressed guy who’d been through several wives, whose beloved son had landed in a mental hospital, who was probably drunk during that brief encounter in his office, who was randomly trying to make himself feel better—none of that occurred to me. I’d heard about the wives, and he’d actually broken down and wept in class reciting “Farewell, thou child of my right hand, and joy,” the first line of Ben Jonson’s elegy to his own son, who’d died at age seven of the plague in 1603. The man’s obvious desolation, his increasingly aimless attempts to cheer himself up, remained invisible to me. I needed a god to worship in order to get through my studies, and he was it.

I was a graduate student at Columbia coping with professors like him—he was far from the only one to say stuff like this to students —when I started my own first teaching jobs. At the time I was going around about in those knife-pleat skirts, twenty-three to the eighteen years of my students, I imagined the problem of their inappropriate feelings would disappear as soon as I looked old enough to be their mothers. It hasn’t. Not even when I was obviously about to become a mother. During my second pregnancy at forty-five, a student in a large class stared at me piercingly for weeks. I assumed this was because I was huge. I had gotten used to colleagues and office workers glancing at me with alarm: She’s-about-to-burst. I paid the staring student no mind.

On the morning I entered the hospital for a planned C-section, I sat checking email in the waiting room while my husband parked the car.

“Dear Melissa,” the missive began, and even in my ultra-pregnant state, warning bells went off. I’d never told this student—or any of my students—that they could call me by my first name. Plus, I was teaching in Germany, where students address professors formally. The email went on: “I really love your classes. You have such a friendly, funny way of speaking. I look forward to seeing you. I’ve been to your husband’s classes too—but I find his lectures boring. He talks in a monotone and is not so interesting. But your classes are wonderful—”

I stopped reading and put my hand on my belly. The baby had started kicking as if he, too, felt startled. I wish I could say my first thought was to feel outrage that my student was insulting my husband, but instead I marveled at this kid’s admiration, glancing at my reflection in the glass door, later at a mirror. I was gigantic, with bags under my eyes. Middle-aged lines had deepened in my face, which pregnancy had aged. I hadn’t dyed my hair in months. Grey roots I couldn’t wait to hide sprouted from my disheveled head. I felt, and looked, anything but glamorous. Yet this young man who stared found me attractive. Or he said he did, which was almost as pleasant. I glanced at the email again. He had a question about the term paper format and when I would be holding office hours.

“Dear Herr Weber,” I typed, “Yes, you may write on this topic. Requirements are available on the university website. Please leave your term paper with the secretary, Frau Gerhard.” I signed the email “sincerely” and used my “Dr.” title. I never had a problem with that student again.

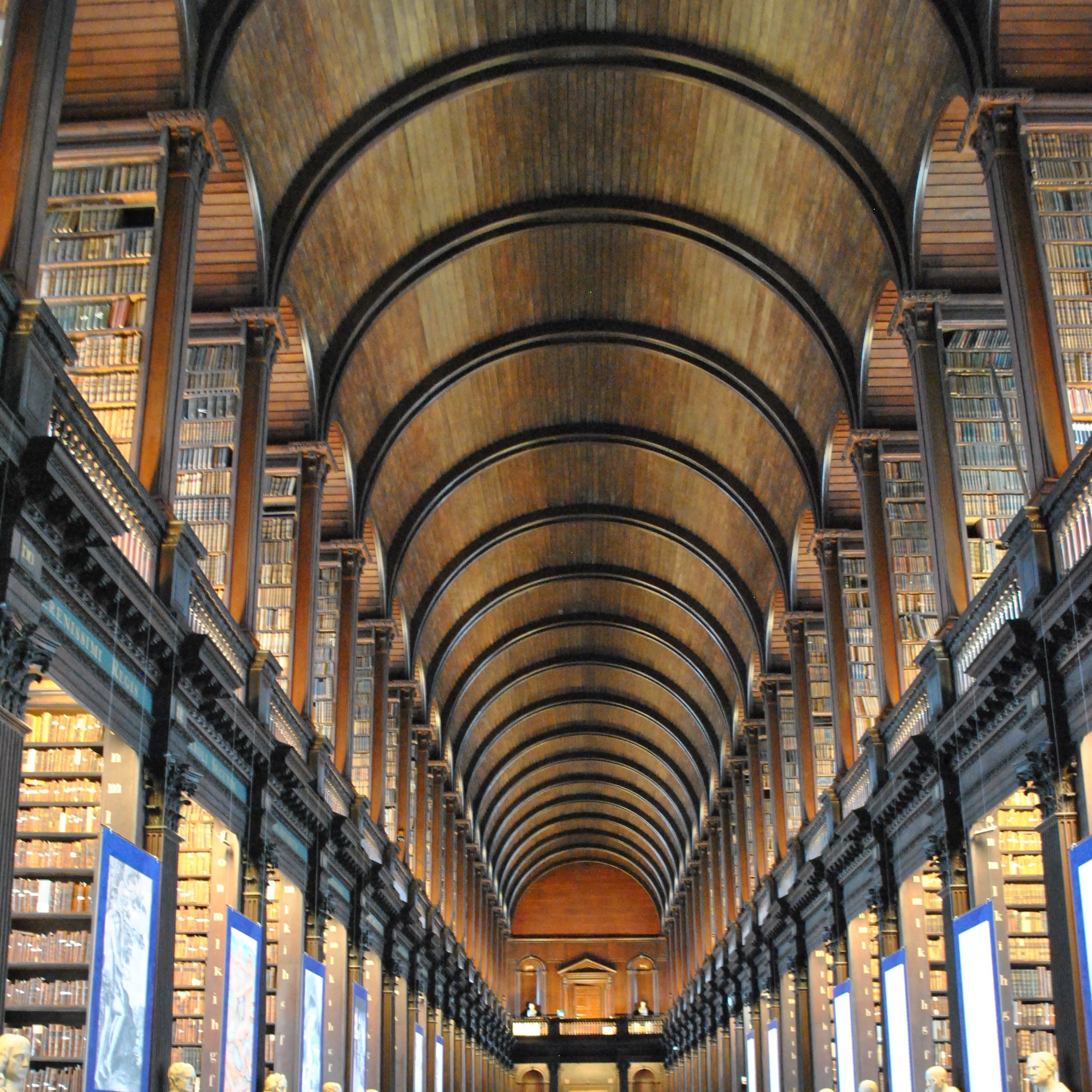

But now, now, even now, when I’m two years short of mandatory retirement—a slightly overweight person in late middle age with the ropy neck of the postmenopausal lady—stuff still happens. I’m on a Zoom call with colleagues, including one who seems wound up about data protection and the length of time it takes to grade a term paper. He’s got grey in his beard, but I’m still old enough to be his mother. I’m sitting in front of a bookcase holding my laptop—we’re all greeting our on-screen selves—when he grins and says, “Hey, Melissa! You’ve got porn on your bookshelf!” His eyes gleam, as if he expects me to jump up, flail my arms, frantically search for the porn and awkwardly try to hide it. I wait a beat, hoping one of our colleagues will say something—mention the remark isn’t funny. Nobody says a word. Their eyes broadcast the wish not to have heard what he just said.

Raising an eyebrow, I speak casually, flirtatiously. “You know my bookshelf better than I do.” Do I wink? I wanted to.

His eyes widened. Disappointment? Shock? He fell silent, and I tried not to smirk. I’d killed two birds with one stone: I’d deprived him of the rise for which he hoped, and—what filled me with private glee—thrown him off-balance. The moment in which I watched him wondering whether ancient me was flirting remains delicious. Yes, I had discerned fear in his rabbity gaze.

Here is what I felt tempted to say to the young man:

“We do have hundreds of books. I’m sure I can find some porn. I just know there’s a seventeenth-century gynecology textbook up in the study, captioned in Latin. We’ve got Erotica Universalis—which takes you from phallic cave wall designs right through Tom of Finland and beyond. Oh, look! Just found some nineteenth-century porn in the pile on my floor for you—A Night in a Moorish Harem! Shall I scan and send?”

Such a response might have had the same effect on him as the formal, distancing behavior I employ with inappropriate student reactions. It would indeed have been fun to bring a blush to his cheek with this lengthier riposte, but that might have been overkill, and overkill can backfire.

Curiosity got the better of me, so after the meeting ended, I closed my laptop and looked for porn supposedly tucked away on my bookshelf. There sat Haruki Murakami’s short-story collection, Desire. Which has a bright red cover.

Maybe that’s the last time I’ll ever have a problem. Looking back, the young student who said I was a good-looking teacher was pointing out that I wasn’t being myself—that it is possible to be your real self without play-acting some lunatic notion of the part—and do a good job. I should have learned, then, to relax, but relaxation comes with confidence, and confidence with experience. If I manage, these days, to subdue a grey-bearded but provocative youngster, maybe that’s because I began to learn from the kid who called me out for my fake grown-up poise and the Columbia professor who exploited it

Nine-tenths of teaching success lies in the ability to observe what students are able to absorb. The character of a class composed of individuals and the trust, or lack of trust, washing over a teacher on the first day of class remain the most important forces in the room. Now that I’ve got what I need in the confidence department, it is, alas, time to retire—not quite as good-looking a teacher, but a good one.

Melissa Knox's recent writing appears in Parhelion, Areo and on substack at Fairforall.org. Read more of her work here: https://melissaknox.com. She lives in Germany.